We identified our NGOs in an attempt to choose organizations that had different impact methodologies. International Medical Corps is classified as an EMT type 1, an international first responder to emergencies, and provides on-the-ground care to those in need. Mercy Ships also provides healthcare to vulnerable populations through the use of a portable hospital ship, focusing mostly on coastal areas, to provide care to areas that may lack it. Project HOPE and Partners in Health both have impact goals based on the education of new healthcare workers through educational programs as well as through the distribution of health supplies. Save The Children is a mix of the two methodologies that work to improve the lives of children through both the expansion of education and healthcare.

We chose this approach to find standardized averages to compare within our metrics that may more accurately reflect the Health and Wellness SDG as a whole. Our process to determine these most important metrics began with research into our chosen NGOs, searching through the websites and annual reports of these organizations and determining the metrics that they most commonly reported. We listed those metrics for each organization before cross-referencing them with the other organizations as well as IRIS metrics to find those that we found to be the most commonly reported as well as those that IRIS reported as significant. After our original research, we determined that while many impact investors are socially motivated, they also expect a return on their investment, thus leading us to the conclusion that many of the most important metrics would be financially based.

We found that metrics such as CEO salary versus the salary of the average employee could help us to visualize the way in which money flows within these organizations. For example, Dr. Gary Gottleib, the current CEO of Partners in Health, stepped down from his previous position in Partners Healthcare and took a nearly $1.8 million pay cut in order to participate fully in Partners in Health. This displays individuals acting starkly outside of the interest of their own financial gain in order to pursue a social mission and instills trust within the organization as well as among their leaders.

We chose the Vulnerable Populations Reached metric which allows us to determine exactly who the social enterprise is reaching out to, and who their work is aiming to assist. By ensuring transparency in their goal and the individuals that are actually receiving aid, investors can determine whether or not the population in need aligns with their own investment goals and passions for their social impact. For example, Mercy Ships focuses on countries along the shores of Africa. So, if an investor likes their specific business model and how they reach people in need of healthcare, they can easily align their own goals with this organization.

The "How Many Lives are Impacted?" metric is similar to the metric of “Vulnerable Populations Reached,” this metric gives investors a numerical look into how many lives have been impacted by the NGO in question. Regardless of the way, the population was impacted, (the construction of a hospital, training programs, supply distribution, etc.) we can look into the number of people receiving aid from the NGO. This number is impacted by the number of years an NGO is operating, and we propose to not measure this number in a linear fashion, but rather to look at the lives impacted per year, as a newer NGO may have impacted fewer people in their beginning stages but would ultimately be a very effective player in the social impact field as they mature.

We found, "Percentage of Donations Going to The Cause" to be one of the most important metrics, especially with regards to the Red Cross scandal, where it was revealed that 25% of donations to Haiti were actually spent on their own internal costs. As a result, trust in the organization tanked, even though the Red Cross needed to spend money on internal costs in order to provide aid. By presenting the percentage of donations going directly to the group’s cause up front, there will be no surprise with regards to operating costs versus the amount of money donated to the mission. Further, we propose to determine a common amount spent on internal costs (within our NGOs, it was around 20%) and have NGOs compare their number to this average.

The other metric is the Percentage of Donations Going to Operating Costs. To make even more transparent operations throughout the organization, we would like organizations to report the percentage of their funding that goes towards internal operating costs. By reporting this number, investors would not only be able to see what amount of their money is

going to internal costs but organizations would also be held responsible for extraneous operating costs, reducing their likelihood of spending money for the sake of spending it, as they would face consequences from investors who want to see a large portion of their money going towards the cause they are donating to. We understand that large organizations have large operating expenses, especially in regards to those who face particularly challenging issues (consider the comparison between an organization building hospitals versus training professionals, cost of materials for that project). This acknowledgment would be reflected in our prototype through an audit of a number that we find to be a fair operation cost for the organization individually.

The "How many professionals trained?" metric reflects a tangible impact that an NGO is providing with regards to increasing human capital in a vulnerable population, beginning a ripple effect geared to opening an employment industry. This metric is most important for NGOs working in the health and wellness sector, but could also be reflective of those in other SDGs such as conservation, as the training and teaching of individuals can lead to a greater impact over the course of generations.

The "caregivers employed" metric allows us to measure the scale of the NGOs’ operations. As more caregivers are employed, it is evident that the NGO is making a significant contribution to the population as a whole by not only providing jobs for those who already have the skills to use but also making available a better quality of care for those who may need it. As stated above, this can be reflective of a hospital being built and providing a workplace for those who already possess the skills to use within the medical field, but can also be reflective of those who have received professional training and are then employed upon completion.

We also had, the "How far does one dollar go within each NGO?" metric. We found that many NGOs advertised the length at which a dollar can make an impact within their purpose. Some NGOs, such as International Medical Corps, advertised that each dollar can be considered multiplied by as much as 30x its worth when put towards their project. The money is multiplied by their sponsors who match donations. So if an investor gives a company $10 and it's multiplied by 30x, the organization receives an additional $290 from sponsors. This metric can, however, be reflective of where the NGO is working and inflation within that area, but is an important statistic to note for investors who may not have large amounts of money to donate but are still looking to make a larger impact. NGOs with a higher multiplier tend to have stronger relationships with their corporate sponsors and receive a larger total amount of donations since they are able to bring in companies to match individual contributions.

We found this "What is the salary of the CEO?" metric to be an interesting and extremely important metric for NGOs, and found that many NGOs aren’t entirely transparent with the salaries of their CEOs and executive board, and our research had to venture to outside sources to find this information. For groups whose mission is centered around impact, it is important to note whether or not the founders are taking an enormous salary for themselves that is mostly, if not entirely, funded on donations. Similar to the percentage of donations going towards operating costs, investors deserve to know how much of their donation may go straight to an individual’s pocket. By making this number transparent to investors, CEOs who take an unethically large portion of money for their own salaries may find it harder to gain support from investors, feeling pressure to participate in more ethical financial practices that would increase their social impact. This would reduce unnecessary spending and encourage executives to act in morally withstanding ways with their finances, reducing greed.

"What is the salary of the average employee?" is another important metric for investors to judge the morality of an NGO based on the salary of the average employee. This metric would need to be judged alongside the salary of the CEO as well as operating costs in order to fully understand the scope of financial practices within the organization. Employees working for these NGOs deserve a living wage for their work, and if decent wages are not reflected within the organization, alongside high operating costs and a high CEO salary, that is a significant signal of unethical financial practices within the organization. However, many NGOs operate on fairly low salaries that are tax deductible and not

meant to be an individual’s sole source of income. It is very important to not look at this metric on its own, but rather to compare it to other related metrics, as stated above.

The "number of employees" metric gives us a good look at the size of the NGO and the impact they are making. However, it is important to compare this metric with the number of volunteers an organization has to judge its distribution of paid work to volunteer work. A higher proportion of paid employees could indicate a higher skill set required to complete the tasks required, reflected in NGOs such as International Medical Corps, a first responder organization who recruits individuals with a medical background, who likely cannot afford to work entirely on a volunteer basis (consider student loans for doctors versus an individual working without a professional degree).

The "number of volunteers" metric is important to judge the scale of impact of an organization but should be considered alongside the number of paid employees, as well. An extremely large volunteer base could signal the fact that the organization is putting most of its money into the cause and is able to recruit volunteers to make a larger impact without the incentive of a salary. Partners in Health and International Medical Corps both did not disclose their numbers of employees. However, this metric is also important to be considered alongside operating costs and the salaries of executives within the organization to ensure that the NGO is not shirking the responsibilities of paying their workers fairly in order to raise a larger profit for themselves.

It is important to judge an NGO’s social media presence in order to judge their interaction with the community around them, as well as to see how they respond to potentially bad press or opinions about their organization. Social media has proved to be an extremely effective tool for citizen journalism and whistle-blowing from previous employees and volunteers and holds organizations accountable for potentially unethical practices. While social media presence is not the most vital judge of an organization’s character or credibility, it gives us good insight into the way the organization may interact with individuals in real life and the way in which they curate their image. Judging those who endorse or follow the organization, and those who the organization itself endorse or follow also provides important information on the way the organization may run. An organization that endorses celebrities who greenwash their own impact may signal that they are not as effective or trustworthy as they may claim, and might warrant an investor to give a second look into their impact before donating.

The other metric is "Are they recognized/respected internationally?" The impact that many of these NGOs have is largely based on countries abroad, and their international recognition is a large signal to whether their impact is effective or not. It is not uncommon for groups to enter a country in need, enact “aid,” but ultimately leave the affected population worse off than when they began, because their impact was not sustainable and created a dependency on the group’s aid that could not be sustained after the NGO moves on. An international recognition, and more important, international respect, signals that these groups have done the research and made an effort to make a sustainable impact that can be withheld and passed on once they have left the area. This implies sensitivity and knowledge of what these communities truly need, and an effort made to ensure that these needs are met in a way that will hopefully prevent the necessity of an aid group’s return.

Our other metric is "are they first responders to global events?" Not every group can be a first responder, but if an organization signals that they are, indeed, a first responder, this is a significant sign of their efficacy and ability to give aid to especially vulnerable populations when they need it most. Within the SDG of health and wellness, not all of the NGOs we chose to focus on actual first response work. Some of the NGOs’ focus is on the education of healthcare professionals, but those who are certified as first responders display special effectiveness and responsibility to work under extreme pressure, with little room for error. These credentials are extremely respectable, and organizations that are trusted to be first responders are likely extremely effective in their work and have proved their credentials in order to be trusted with this work.

The "who/what are their corporate sponsors?" metric is important because an organization’s corporate sponsors are often a reflection of its values. Corporations often act self-serving and donate large amounts of their money to organizations that may ultimately serve their personal interests, so it is vital to vet not only the organization itself but those who support them. Health organizations that are supported by other doctors and professionals in the field are likely far more trustworthy than those who are supported by corporations who are known for their own corrupt financial practices and may be supporting an organization solely out of their own self-interest.

An increase in corporate social responsibility during the 2000s has led to increased corporate activity within NGOs, as it grants them with an image of goodwill and marketability, but several reputable organizations have been known to deny sponsorships to corporations that they find to be corrupt. The partnership between NGOs and their corporate sponsors is often reflective of their true values and the extent to which they are willing to compromise their values for the sake of donations and provides insight into the NGO and their goals.

"Any unique services performed?" is the final metric that provides some organizations a leg up on others, highlighting a service they may perform differently. This allows organizations that go above and beyond in terms of their goal and gain the recognition they deserve for doing such. This metric should not be seen as a deal breaker in whether or not an investor decides to donate, for NGOs can make a very large impact without a completely unique service, but rather as an enrichment to those organizations who have received special recognition or are acting within a niche sector that has not yet been explored. To make our metrics scalable, we have created a template that assigns NGOs scores of 1-5 based on the standards of their answers against each of the other philanthropies selected.

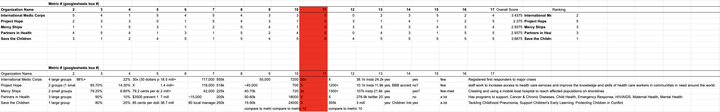

We also considered how we want the metrics as above. We first collected data on all the NGOs based on the information they had available. We then took that data and turned it to make it comparable between different NGOs. For example, when comparing vulnerable populations reached, we first analyzed the number of populations reached and then how specific/small that population was. This allowed different population types to be comparable. Bigger populations and a larger number of populations would be ranked higher. We created the scores comparatively between the NGOs. We compared NGOs’ data based on what we found important about the metrics as described above (ex. ranking employees’ salaries while considering CEOs’ salaries and making sure they have a livable income).

The score was then administered by comparing NGOs’ data. Better performing NGOs would score higher and similarly performing NGOs would be scored equally. NGOs who did not provide the information for the metric would get a 0 (the only way to score a 0). This is because our system values transparency and NGOs who do not report all metrics should receive a penalty. After giving each NGO a score out of 5 based on their metric, we added all of the scores together and took an average of the final out of the total points, leading to an overall score that falls between 1-5. Lastly, we ranked the NGOs based on their overall score to have a “winner,” or an NGO with the highest overall score. This system allows us to rank, score, and compare NGOs based on metrics in a way that allows us to measure NGOs adherence

to the values we hold.

This will therefore then allow investors to assess and compare which NGOs to best donate their money to, allowing better investments to occur. In a larger prototype, with a bigger pool of data (more NGOs), we would want to create a “guideline” to create standard numbers that are associated with specific scores. For example, A CEO's salary of 150,000 or less is a 5, a CEO's salary of 150,000-250,000 is a 4, etc. This would make the system more objective. Especially important to investors is to know where their money flows within an NGO once it is donated, which is why so many of our metrics relate directly to finances. This is an attempt to shed light upon cash flows as well as hold NGOs accountable for spending that may be abusive of their donations and mission.

While transparency is the norm for NGOs, who often stay true to their mission and act in ethically upstanding ways, it is important to hold those who may stray from that standard accountable, and we believe that an increase in transparency across all NGOs will lead to a universal push to the most ethical standard. Those who act best according to positive metrics will find themselves high scoring across our template, and as a result, will receive the positive reinforcement of increased investors. Some limitations within our template include the fact that our template requires standards

deemed “good” or “bad” for NGOs to abide by, such as an acceptable percentage going towards operating costs. Within our research, we found that about 80% of funds went towards operating costs from our NGOs, but this does not address others who may have higher expenses, such as those building hospitals.

Further, costs of operation and costs of employees are not standard in all geographic areas, so the standardization falters as NGOs operate from different areas. Doctors from the West may be unwilling to work without the high salaries they are accustomed to, while doctors from other countries may be amicable to more volunteer work and lower wages. Further,

the cost of educating individuals would likely be less than the cost of building hospitals, leading to different operational and mission costs for each NGO based on their individual goals. To address these limitations, we would take rolling averages from hundreds of NGOs across all different SDGs in order to determine numerical standards with which to hold our NGOs accountable. For the purpose of our project, we utilized averages calculated from our five chosen NGOs and scored from those numbers. To fully standardize our metric, we would like to expand our research across all SDGs with many more NGOs to compare.

In conclusion, we believe that it’s essential for NGOs to be as transparent as possible for impact investors. The more common information that NGOs provide to the public, the better it is for investors to choose the right NGO for their personal impact goals. Throughout our extensive research of the five following NGOs: International Medical Corps, Mercy Ships, Partners in Health, Save the Children, and Project Hope, we found many common metrics each organization provided, and some metrics, such as the number of volunteers, that some NGOs did not report, and we would like to see that lack of reporting remedied.

Loading ...

Loading ...